IS MURDERING OF GOATS ON BAKRI EID,

A TRUE SACRIFICE ?

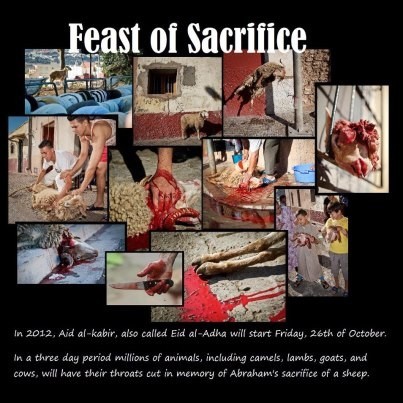

Sprinting down the road is a goat, dirtied and tagged green by its owners. It is running hard, yelping for a reprieve. It will have none, as the owners, smiling and laughing catch up to the young animal and begin dragging it back toward its final resting place. The sounds of screams leave no doubt the animal is in pain. It’s legs are cut, blood dripping from limbs.

“It’s so it doesn’t run away again,” said one of the owners, knife in hand and blood from an earlier sacrifice staining his clothes.

There’s another goat tethered inside an area that could be no larger than 10 feet by 5 feet. There were three goats, the men standing around admit. They feed from a small bowl filled with leftovers in one corner. Waste is strewn throughout the little pen. In less than five minutes, the goat that ran down the street, screaming for its life is tied to the wall, and immobilized by its captors.

Then, a man steps forward, knife in hand and makes a move to the animals throat. A horrifying scream is released from the animal. The men step back and blood begins to cover the ground below. The animal is dying. It is not a quick death, despite advocates of the method of killing. The goat squirms, attempting to run, but it has no energy and after a few minutes of struggle it lays limp on the ground. It is dead. It couldn’t escape.

The sacrifice is part of the Islamic holiday Eid al-Adha. For the vast majority of Muslims worldwide, it is tradition and one they believe is necessary for showing their submission to God’s will. For others, however, the three-days of sacrifice has become a symbol of cruelty, violence and disgust.

This Eid al-Adha holiday, thousands upon thousands of sheep, goats will be killed on a street near you. As animal rights organizations continue to cry foul, cultural tradition and faith often converge, avoiding any real dialogue on the public slaughtering and cruelty of animals in Islamic societies, in the name of religion.

Sheikh Yussif Gama’a of Egypt’s al-Azhar – the world’s leading Sunni Islamic institution – said that the sacrifice is “symbolic of Abraham’s test in front of God.”

Gama’a argued that by sacrificing an animal – sheep, camel or goat – one is able to show piety and allegiance to the divine. “It is part of the tradition of submission central to Islam and our ability to follow God’s instructions at all times.”

Yet, he pointed to how the sacrifice has become tradition more than a matter of faith, and for him, this is vital in understanding how Islamic societies may be able to “modernize” the sacrifice.

“Islamic scholars often look at things without a historical context and this takes away from the most important aspect of religion – faith – so we must be careful that something does not become a ‘that’s how it has always been so don’t tell us otherwise’ mentality,” he added.

The sacrifice originated in Bedouin society over one thousand years ago as a means of promoting an understanding of faith. It was meant to bring a society that, at the time, was starkly different than today. Bedouin culture is nomadic and by having a sacrifice Muslims from all walks of life were able to be unified and celebrate their infant religion.

Coming directly after the Hajj pilgrimage, it was meant to signify the progression of faith and one’s sacrifice to God. Today, it seems almost unnecessary, even overly violent and backwards to many, especially the growing animal rights community in the region.

This Eid, dozens of online groups have been established in an attempt to end the slaughtering of hundreds of thousands of animals. The uphill battle they face is a combination religion and tradition, said Amira Hassan, an animal rights advocate and devout Muslim woman from Hyderabad.

“We need to examine why this continues to exist, because it is detrimental to our society as a whole,” she began. “The way we treat animals, tying them up, slitting their throat and letting them suffer in agony for minutes or hours because we want to abide by a religious tradition should be looked at closely.”

For Hassan, the argument is similar for the Islamic world. “We are no longer living in a Bedouin society and the historical context that was when the sacrifice began no longer exists across the Islamic world, so why do we persist in killing in the name of God beings that are to be respected?”

Tell that to butcher Ahmed Abdallah, who pointed to the rows of meat hanging from his shop, saying “it is our right as humans to slaughter and use animals for our purposes. It is written.”

Historically, Bedouin traveled with animals, used them as part of their life. Thus, the sacrifice was truly a sacrifice of giving. One was forced to give a part of their livelihood and through the sacrifice one-third of the meat was given to the family, one-third to the poor and one-third to friends. It was symbolic of giving something close to one’s heart.

Today, most families simply purchase an animal, feed it in the weeks leading up to the slaughter and then kill it when the day comes.

She leaves the country in order to avoid seeing the blood-stained streets and the squeals of animals being slaughtered, she admitted.

“Islam tells us we are to treat all sentient forms with respect and dignity, and while it is permissible to eat meat in our religion, it is important to note that the sacrifice may no longer be about community but maintaining a historical tradition that is no longer part of the modern Islamic society.”

The Qur’an says “It is not their meat nor their blood that reaches Allah; it is your piety that reaches Him.” (Qur’an 22:37)

Thus, We don’t get closer to God by killing, we get closer to God by showing compassion and understanding, including to the animals that we use to live.

For the hundreds of thousands of animals slaughtered on Friday in the name of religion, at least for their relatives, the future might be more humane, if activists can get the message across.

CAclubindia

CAclubindia